Nature Divine

by Bonnie GangelhoffSouthwest Art

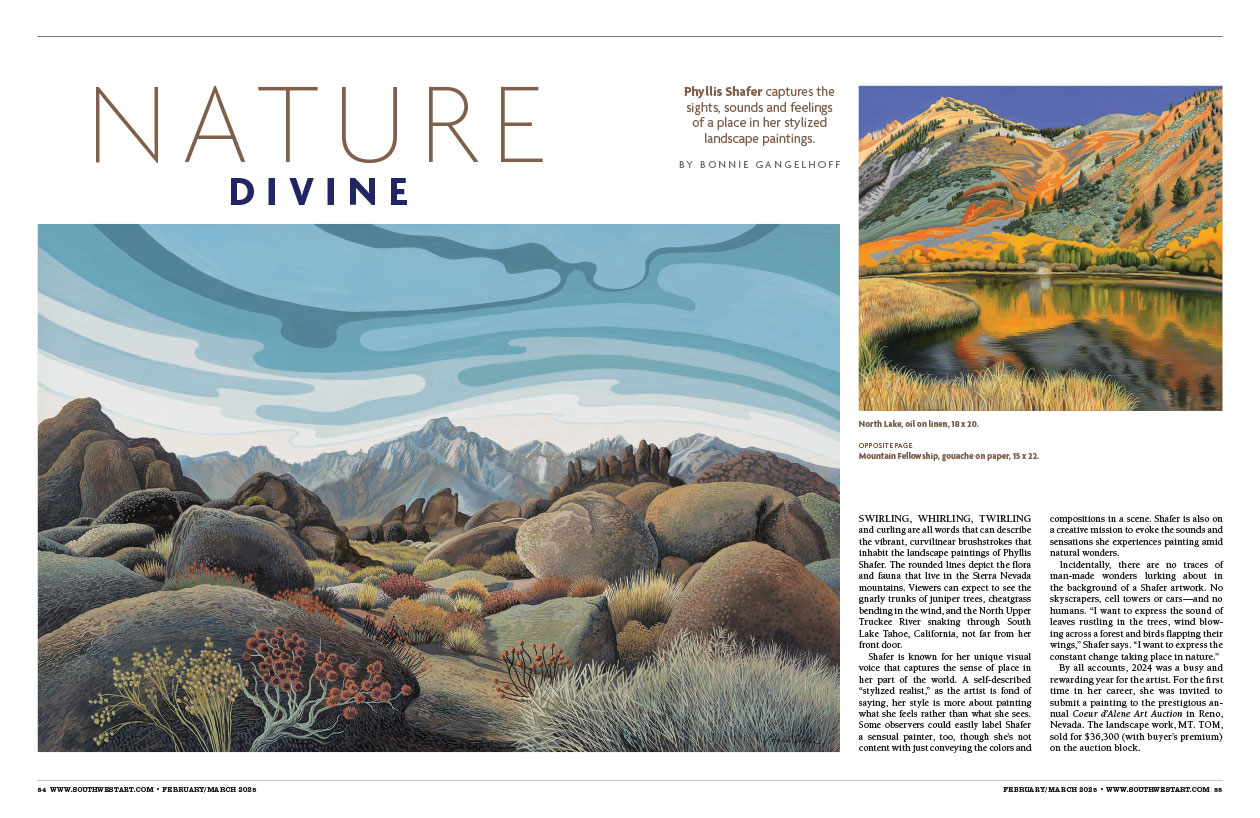

Swirling, whirling, twirling and curling are all words that can describe the vibrant, curvilinear brushstrokes that inhabit the landscape paintings of Phyllis Shafer. The rounded lines depict the flora and fauna that live in the Sierra Nevada mountains. Viewers can expect to see the gnarly trunks of juniper trees, cheatgrass bending in the wind, and the North Upper Truckee River snaking through South Lake Tahoe, California, not far from her front door.

Shafer is known for her unique visual voice that captures the sense of place in her part of the world. A self-described “stylized realist,” as the artist is fond of saying, her style is more about painting what she feels rather than what she sees. Some observers could easily label Shafer a sensual painter, too, though she’s not content with just conveying the colors and compositions in a scene. Shafer is also on a creative mission to evoke the sounds and sensations she experiences painting amid natural wonders.

Incidentally, there are no traces of man-made wonders lurking about in the background of a Shafer artwork. No skyscrapers, cell towers or cars—and no humans. “I want to express the sound of leaves rustling in the trees, wind blowing across a forest and birds flapping their wings,” Shafer says. “I want to express the constant change taking place in nature.”

By all accounts, 2024 was a busy and rewarding year for the artist. For the first time in her career, she was invited to submit a painting to the prestigious annual Coeur d’Alene Art Auction in Reno, Nevada. The landscape work, Mt. Tom, sold for $36,300 (with buyer’s premium) on the auction block.

Then in November, Shafer’s paintings View to Mt. Tom and Owens River Gorge were on view in a group show at the “re-re-opening” of Maxwell Alexander Gallery in Pasadena, California. Her brushstrokes create a lively dance of lines in View to Mt. Tom that suggest enough movement among the rabbitbrush, sage, cheatgrass and bitterbrush that the plants could skip right off the canvas on this seemingly windy day. In the painting, another recurring element in Shafer’s art unfolds—a detailed foreground and a large expanse of terrain reaching toward mountains in the distance.

“I see nature as a metaphor for my own passage through life,” the artist says. “I find solace in seeing the vastness of the deep space juxtaposed against a tiny, exquisite microcosm at my feet. Nature helps me see my own trajectory from youth to older age and beyond.”

Shafer often exaggerates the scale of flora and fauna in her landscapes. Take the painting Clark’s Day Out. A mule ear flower and a gathering of Clark’s nutcracker birds are portrayed larger than life. The distortion and exaggeration bestow a touch of the surreal and magical on the scene. And there’s a blurring of the boundaries between reality and fantasy. The painting also features waves of puffy white shapes sprawling across a blue sky, suggesting clouds are on the move and change is in the air. One observer noted that Shafer’s depictions of clouds are at times reminiscent of “smoke curling from a magic lamp.”

The setting for Clark’s Day Out is California’s Lake Winnemucca near Kit Carson Pass in the Sierras, a favorite hiking and destination for Shafer and friends. “Winnemucca Lake is an iconic hike for everyone who lives in South Lake Tahoe,” the artist says. “I wanted to do this painting to pay homage to this iconic hike for us locals.”

When citing influences on her art, Shafer first points to Thomas Hart Benton (1889-1975), saying she relishes “the rhythmic, undulating distortion he brings to his works.” Benton was a Midwestern regionalist painter, but he was also known as part of the modernist movement, a cadre of artists that worked from about 1910 to the 1940s. The American modernists, such as Benton, Georgia O’Keeffe (1887-1986) and Charles E. Burchfield (1893-1967), wanted to break away from traditional conventions and forms. Like Shafer, they were known to distort reality rather than render it in a tight, photorealistic style.

No matter how viewers, critics or collectors describe Shafer’s paintings, the artist explains that the soul of her work ultimately lies in the Zen Buddhist concept in painting called kiin-seido. “What appeals to me is their idea of the living moment or the immediate expression of a subject’s essential nature,” Shafer says. “For me, it is the entire reason why I carry my gear outside and engage in the laborious process of painting on location. It’s to breathe the space and feel its rhythms and try to interpret that sensation in my artworks.”

Shafer grew up in farming communities in upstate New York. She didn’t think about becoming an artist until high school when an art teacher offered encouragement and validation of her talents. After graduation Shafer went on to earn a Bachelor of Fine Arts from the State University of New York at Potsdam. At the time, her professors proclaimed that there were two requirements for success as an artist: move to New York City and do not go to graduate school.

Shafer eventually settled in Manhattan after graduation, living in a fifth-floor walkup and creating fantastical landscape paintings. However, on a road trip to California in 1983, she fell hard for the expansive western terrain and skies. Soon after she packed her bags and moved to Oakland, California. Ignoring the advice of her New York professors once again, she enrolled in the graduate painting program at the University of California, Berkeley.

For a decade Shafer was an active participant in the thriving Bay Area art scene, exhibiting her paintings in both group and solo shows. But after 10 years, change was brewing. A teaching position opened at Lake Tahoe Community College in Northern California and Shafer was ready to answer the siren call. She upended her city life and in 1994 settled in South Lake Tahoe where she remains today. Shafer retired as the co-chair and gallery director of the art department in 2021.

As this story was going to press, the artist had just returned from a three-day painting trip to Bishop, a small town on the east side of the Sierras. Her husband, Mark, had accompanied her in the couple’s camper van. He joined friends on a rock-climbing adventure at the nearby Owens River Gorge and Shafer headed off in a different direction to paint alone in the wild. It’s Shafer’s practice to paint solo so there are no distractions. “I go out and do what I call trawling, searching for a spark,” she shares. “It could be color, composition or light. But mostly I am looking for the relationship between the foreground flora and fauna and the deep vista beyond.”

From November through March, Shafer paints in her studio, completing works she started on location in the warmer months. For 2025 shows, she is currently focused on finishing a painting for the exhibition Romance Reimagined at the Autry Museum of the American West in Los Angeles. A work-in-progress for a November two-person show at the Stremmel Gallery in Reno, Nevada, sits on an easel in her studio.

With at least two shows in the offing, 2025 is shaping up to be another rewarding year for Shafer. In addition, Maxwell Alexander Gallery is producing a limited-edition serigraph of Clark’s Day Out, available to purchase this spring, according to Shafer. And Pomegranate Communications, the high-quality publishing company based in Portland is creating a calendar featuring an array of Shafer’s images from the Sierras. The calendar, titled Nature Divine, perfectly pinpoints Shafer’s thoughts and feelings about the natural environment. For the artist there is a divine spirit that dwells in the wild and in the things she paints. “Nature is my religion,” she says.

When she is “trawling” in the wilderness for subject matter, she is communicating with the divine. She says, “In the end, I paint for myself, for my own spiritual comfort and enlightenment. And if the result resonates with others, I’ve done my job.”

Nature Divine

by Bonnie Gangelhoff

Southwest Art

Records of Reverie

by Chris Lanier

Double Scoop

The Phyllis Shafer Experience

by Richard Polsky

Western Art & Architecture

Tinged with Fantasy …

by Grace Ebert

Colossal

Living Off the Land

by Harriet Modler

American Style

Desert Supplement

by Steven Biller & Deborah Ross

art ltd.

Phyllis Shafer: A Painter’s Journey

by Kirk Robertson

Artweek

Pantheist Visions

by Laura Read

Tahoe Quarterly

Artown ready to ‘Bloom’

by Forrest Hartman

Reno Gazette-Journal